Table of Contents

What is Binge-Eating Disorder?

Binge-eating disorder (BED) belongs to a family of eating disorders. It generally develops during childhood and varies in severity, risk-level, and outcome.

Signs and Symptoms

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by the following signs and symptoms:[2]

- Consuming more food than what most people consume, during a specific time period (usually within a 2-hour timeframe), under similar circumstances.

- Experiencing a lack of control over how much and when food is consumed, feeling unable to stop eating, and significant distress, during binge-eating episodes.

Initially, these “episodes” typically occur, on average, at least once-a-week for at least 3 months, and are not associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors like those found with bulimia nervosa.

These episodes should not occur exclusively, during the course of a bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa episode.

Three or more of the following factors should also be present:

- Rapidly consuming more food than normal

- Consuming large quantities of food until one becomes uncomfortably full

- Communing large amounts of food, when not physically hungry

- Eating alone out of embarrassment due to the amount of food being consumed

- Feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after a binge-eating episode

Note: To be diagnosed with BED, the symptoms must occur at minimum twice-a-week for 6-months and at least once-a-week for the preceding 3-months. [3]

Those with a binge-eating disorder often feel ashamed of their eating problems, and as a result, try to hide their symptoms.

Binge-eating is typically associated with feelings of distress and a loss of control.

This condition can be triggered by personal stressors, an negative body image perception, or even boredom.

Repeated binge-eating episodes are often preceded by a trauma or a negative experience. And, over time, binge-eating episodes can become chronic. [4]

Possible Causes of BED

The exact cause of BED varies from person-to-person.

Some researchers believe that the cause stems from the neuropeptide Y compound found in the brain – a compound that is partially responsible for regulating weight. According to these researchers, this compound can cause several regions in the brain to malfunction, leading to binge-eating.

Other researchers believe that an altered brain circuitry is the cause of BED. According to these researchers, an altered circuitry interferes with one’s internal reward system, leading to a binge-eating disorder.

Most researchers, however, believe that increased brain tissue in the region that controls eating urges, can trigger this disorder. Specifically, these researchers believe that an increase in the brain’s gray matter (brain material) can lead to weight gain and an exaggerated response to positive sugar ratings. [6] Moreover, studies suggest that reduced white brain matter is also linked to BED. [7]

[thrive_custom_box title=”” style=”dark” type=”color” color=”#faf8d7″ border=”#000000″]

BED involves the over-analyzation, overvaluation, and/or intense examination of one’s own body shape and weight.

[/thrive_custom_box]

It is important to note, however, that one’s body mass index (BMI) alone is not linked to BED, which implies that being over one’s ideal body weight is not always associated with this condition.

On the other hand, body shape and weight does appear to be linked to an altered self-esteem and/or a bias towards one’s body size. Furthermore, negative moods are associated with binge-eating – both before and after it emerges, which trigger a lower self-esteem. [8]

BED Risk Factors

While the exact cause of BED varies, there are some significant risk factors such as gender (females develop it more frequently than males) and dysfunctional family interactions.

[thrive_custom_box title=”” style=”dark” type=”color” color=”#faf8d7″ border=”#000000″]

Weight-centered criticism from a parent can place a child at-risk of becoming a binge-eater. This is especially true if that criticism is leveled at the child before he/she turns 10-years-old.

[/thrive_custom_box]

It is important to note that children with BED, over the age of 13, may begin to overeat, gain weight, and voice displeasure with his/her body shape and size.

Moreover, dysfunctional family interactions, especially during meals, may trigger BED in vulnerable children and adolescents. [7]

In fact, a recent study on eye-tracking technology and eating disorders, found that people with eating disorders tend to obsess about the “unattractive areas” (i.e. large buttock, big breasts, wide hips, love-handles, etc.) of their body more often, than those without eating disorders. A preoccupation with “flaws” can lead to distorted thinking and physical distress. [28]

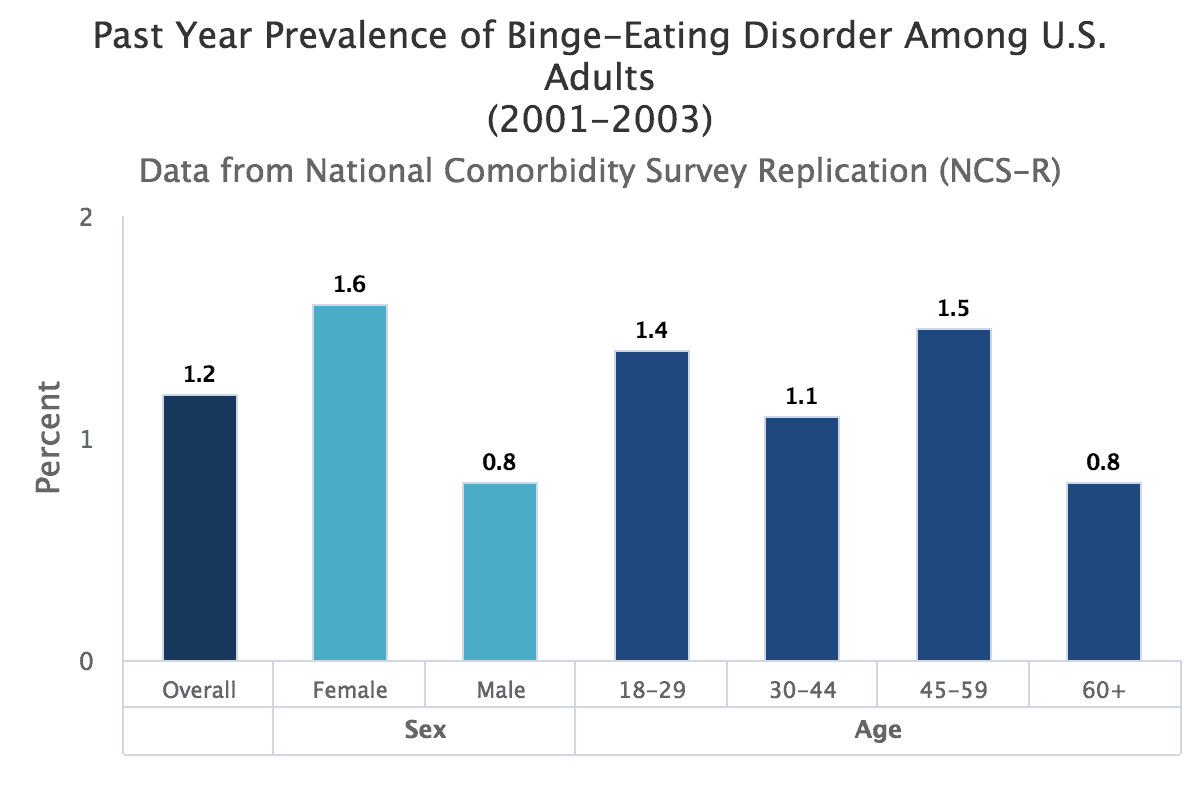

Statistics

Binge-eating is more common in females, who are overweight, who are depressed, and who smoke marijuana and/or frequently engage in illegal drugs (excluding binge-drinking).

Studies suggest that the frequency of overeating or binge-eating generally peaks (3.2 %) by age 19, with 2.3% to 3.1% of females and 0.3% to 1% of males reporting binge-eating, between ages 16- and 24-years-old. [9]

Asian-Americans are more likely, than Caucasian-Americans to report having a BED, but less likely to seek treatment for it. [12]

Also, homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual males with BED have a higher rate of anxiety and drug abuse than those without an eating disorder. Mood disorders are also more common in lesbian and bisexual females with eating disorders than those without eating disorders. [13]

One study found that African-Americans are more dissatisfied with their bodies and more obese, than their white counterparts. However, it important to note that the number of African-Americans study participants was much lower than the number of Caucasian-Americans participants, and thus, should be interpreted with caution.[14]

Another study found African-American women with BED did better with self-monitoring technology than their Caucasian-American female counterparts. [15]

Lastly, a 2017 study on eating disorders revealed that every socioeconomic class is at-risk for this disorder. [30]

According to researchers, the onset of BED occurs at a later age, than the onset of anorexia or bulimia, leading to a more favorable remission rate for BED. However, the severity, duration, and suicide risk appear to be the same for all three eating-disorders.[17]

Below are some statistics from the National Institute of Mental Health regarding Bing Eating Disorders:

So, What Can You Do?

You should consult your child’s pediatrician, if you suspect that he/she is suffering from an eating disorder. Your child’s doctor will evaluate him/her to determine, if he/she has an eating disorder. This medical professional will also rule out any other physical conditions that could be causing or worsening your child’s BED symptoms. In addition, he/she will supervise your child’s medical care. [22]

Your child’s doctor may order a thyroid test to check for low thyroid levels and a genetic test to rule out Prader-Willi Syndrome (a defect in chromosome-15). Prader-Willi Syndrome can cause a person to over-eat. It is important to note that a variety of genetically-linked disorders and intellectual disabilities resemble BED symptoms or increase your child’s risk of developing BED. [29]

Specialized eating-disorder centers can perform certain procedures such as observing the binge-eater’s eating patterns while with family members. [23,24]

Doctors should take every measure to provide appropriate treatment for a binge-eating disorder by determining if treatment should be inpatient or outpatient.[22]

Treatment Considerations

It is rare for people with BED to be hospitalized, unless there are other issues, such as substance abuse or suicidal tendencies. In severe cases, however, or in the case of loneliness, inpatient therapy may be considered.

Nutritionists, counselors, and cognitive behavioral therapists (CBT) will play a crucial role in the recovery process. [10]

Medications

In some cases, medications are needed to help control BED symptoms and aid in the recovery process.

Fluoxetine (Prozac): Fluoxetine is an FDA-approved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for the treatment of conditions like binge-eating disorder (BED), depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bulimia nervosa, and panic disorder. This medication is beneficial for BED because it helps reduce binging episodes.

However, it is important to note that a common side-effect of Prozac is weight gain, so other serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) may be used instead.[5]

lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse): Another drug used to control BED symptoms is lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse). Lisdexamfetamine is an FDA-approved stimulant used to treat ADHD and moderate-to-severe BED.[11,18]

Anti-seizure drugs: these may be used to combat eating disorders like BED. Anti-seizure drugs are often used with anti-obesity drugs, phentermine, lorcaserin, and/or orlistat to curb compulsive-eating by regulating the neuropeptide Y compound.

Keep in mind, however, these drugs can have a wide-variety of side-effects.

Behavior Therapies and Counseling

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is the most effective BED treatment.

A randomized study compared CBT with a placebo to Prozac alone and CBT plus Prozac, and found that CBT alone was just as effective in treating BED as any other treatment regimen.[19]

Family Therapy

If family members are deemed “problematic,” family therapy can help reduce triggers and BED behaviors.

Self Monitoring

Utilizing self-monitoring weight loss strategies, such as keeping a diary of food intake, physical activity, weight-monitoring, and risk-related behaviors like drinking sugar-laden drinks, along with using an electronic tracker or mobile app, can ward-off binging episodes. [15]

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Another useful strategy, developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan, is dialectical behavior therapy. This therapy identifies and addresses relationship issues that can trigger unhealthy emotions. It is beneficial for BED because it teaches the binge-eater how to self-soothe, thereby reducing unhealthy eating behaviors. [20,21]

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality therapy uses modern technology to create awareness and memory and to teach patients to accept their body as normal so they can feel normal as a whole person.[25]

Meditation & Yoga

Mindfulness meditation or insight meditation allows binge-eaters to accurately recognize and acknowledge experiences in a healthy, non-judgmental manner, thus calming fears and impulses.[26]

Yoga has also proved useful helping binge-eaters maintain a stable weight and BMI.[27]

Outlook

Binge-eating disorder is often (but not always) associated with obesity and/or an elevated body mass index (BMI). In fact, many obese people simply overeat on a regular basis, rather than in spurts. And, according to current research, certain metabolic, endocrine, neurologic, hormonal, and genetic factors can predispose someone for obesity.

In addition, anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder are linked to BED, which increases the risk of developing other maladaptive behaviors.

The good news is that long-term monitoring can ensure the safety of the bing-eater, while improving treatment outcomes.

In comparison to other eating disorders, BED is less likely to lead to serious acute complications.

It also has a more favorable prognosis, especially if weight and BMI can be normalized or maintained, than other eating disorders.

Thus, it is imperative that binge-eaters maintain a healthy diet, reduce their stress, and engage in healthy and reasonable physical activity.

References

- Stunkard, A. J. (1959). Eating patterns and obesity. Psychiatr Q., 33,284-95.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th Edition.

- Wade, T .D., Treloar, S. A., Heath, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (2009). An examination of the overlap between genetic and environmental risk factors for intentional weight loss and overeating. Int J Eat Disorder, 42(6),492-497.

- Ahlskog, J. E., & Hoebel, B. G. (1973). Overeating and obesity from damage to a noradrenergic system in the brain. Science, 182(4108), 166-169.

- Flament, M..F., Bissada, H., & Spettigue, W. (2012). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 15(2),189-207.

- Schäfer, A., Vaitl, D., & Schienle, A. (2010) Regional grey matter volume abnormalities in bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Neuroimage, 50(2), 639-643.

- Pearl, R. L., White, M. A., & Grilo, C. M. (2014). Overvaluation of shape and weight as a mediator between self-esteem and weight bias internalization among patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Behavior, 15(2),259-261.

- Smink, F. R., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 14(4):406-414.

- Sonneville, K. R., Horton, N. J., Micali, N., Crosby, R. D., Swanson, S. A., Solmi, F., et al. (2013). Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: Does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatrics, 167(2),149-155.

- Treasure, J., Claudino, A. M., & Zucker, N. (2010). Eating disorders. Lancet, 375(9714), 583-593.

- Cassels, C. (2015) FDA okays Vyvanse for binge eating disorder. Medscape Medical News.

- Lee-Winn, A., Mendelson, T., & Mojtabai, R. (2014) Racial/ethnic disparities in binge eating: Disorder prevalence, symptom presentation, and help-seeking among Asian Americans and non-Latino whites. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7),1263-1265.

- Feldman MB, Meyer IH. (2011) Comorbidity and age of onset of eating disorders in gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Psychiatry Res, 180(2-3),126-131.

- Fernandes, N. H., Crow, S. J., Thuras, P., & Peterson, C. B. (2010). Characteristics of black treatment seekers for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disorder, 43(3),282-285.

- Steinberg, D. M., Levine, E. L., Lane, I., Askew, S., Foley, P. B., Puleo, E., et al. (2014). Adherence to self-monitoring via interactive voice response technology in an eHealth intervention targeting weight gain prevention among Black women: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res, 16(4),114.

- Steinhausen, H. C. (2009). Outcome of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 18(1), 225-242.

- Franko, D. L., Keshaviah, A., Eddy, K.T, Krishna, M., Davis, M. C., & Keel, P. K. (2013). A longitudinal investigation of mortality in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry, 170(8), 917-925.

- McElroy, S. L., Hudson, J. I., Mitchell, J. E., Wilfley, D., Ferreira-Cornwell, M. C., Gao, J., et al. (2015). Efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine for treatment of adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder: An randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry.

- Grilo, C. M., Crosby, R. D., Wilson, G. T., & Masheb, R. M. (2012). A 12-month follow-up of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol,80(6),1108-13.

- Klein, A. S., Skinner, J. B., Hawley, K. M. (2013). Targeting binge eating through components of dialectical behavior therapy: preliminary outcomes for individually supported diary card self-monitoring versus group-based DBT. Psychotherapy (Chic), 50(4),543-552.

- Fischer, S., & Peterson, C. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent binge eating, purging, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury: A pilot study. Psychotherapy (Chic).

- Katzman, D. K., Peebles, R., Sawyer, S. M., Lock, J., & Le Grange, D.(2013). The role of the pediatrician in family-based treatment for adolescent eating disorders: opportunities and challenges. J Adolescent Health, 53(4), 433-440.

- Wilson, G. T. (2011). Treatment of binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clin North Am, 34(4), 773-783.

- Hay, P. (2012). A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005-. Int J Eat Disorder,46(5), 462-469.

- Riva, G. (2014). Out of my real body: cognitive neuroscience meets eating disorders. Front Hum Neuroscience,8, 236.

- Woolhouse, H., Knowles, A., & Crafti, N. (2012). Adding mindfulness to CBT programs for binge eating: A mixed-methods evaluation. Eating Disorders, 20(4), 321-39.

- Carei, T. R., Fyfe-Johnson, A. L., Breuner, C. C., & Brown, M. A. (2010). Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. Journal Adolescent Health,46(4),346-351.

- Bauer, A., Schneider, S., Waldorf, M., Braks, K., Huber, T. J., Adolph, D., et al. (2017). Selective visual attention towards oneself and associated state body satisfaction: An eye-tracking study in adolescents with different types of eating disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology.

- Bulik, C. M., Hebebrand, J., Keski-Rahkonen, A., Klump, K. L., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Mazzeo, S. E., et al. (2007). Genetic epidemiology, endophenotypes, and eating disorder classification. Int J Eat Disorder, 40, 52-60.

- Mulders-Jones, B., Mitchison, D., Girosi, F., & Hay, P. (2017). Socioeconomic correlates of eating disorder symptoms in an Australian population-based sample. PLoS One, 12(1).